The Federal Government and Debt

Home >

Article 1, Section 8, of the U.S. Constitution empowers Congress to borrow money against the full faith and credit of the government. And since its beginning as a sovereign nation, the U.S. has borrowed money and amassed debt.

Why? Because it was universally agreed among the Founding Fathers, that borrowing money to finance their revolution was an absolute necessity. Alexander Hamilton, our first Treasury Secretary stated that: “The United States debt, foreign and domestic, was the price of liberty.” And because the government’s expenses often exceeded its income.

Except for a brief period under President Andrew Jackson, when U.S. debt shrank to zero, the national debt has been a part of the government’s overall economy. At times it grew slowly, at times it was whittled down and at times it exploded. But to this day, it has not been repaid fully.

For instance:

- By the end of the Civil War, the national debt was $2.7 billion.

- By the end of World War I, it was $22 billion.

- The Great Depression and the buildup to World War II brought it to $51 billion.

- And it reached $260 billion after World War II.

Given the amount of U.S. government debt, it’s hardly surprising that Americans have assumed spending habits that rival those of Congress.

Modern Federal Debt

During the post-war years, the debt’s growth matched inflation, but it more than tripled between 1980 and 1990. It dipped briefly after the end of the Cold War, but by the end of 2008 the nation’s public debt had reached $10.3 trillion – 10 times its 1980 level.

The government’s debt actually consists of two components:

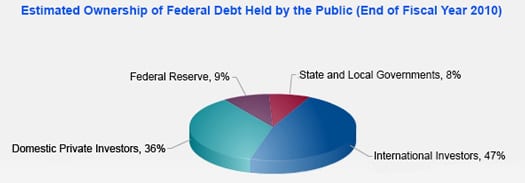

- Its public, or marketable, debt (treasury notes, bonds and bills) is held by investors outside the federal government. These include individuals, corporations, the Federal Reserve System and foreign, state and local governments. As of February 2012, $5.1 trillion, or approximately one half of the debt held by the public, was owned by foreign investors, the largest of which are China and Japan who both own over $1 trillion in treasury securities.

- The second component is intra-government debt in non-marketable securities. These are held in government accounts such as the Social Security Trust Fund but owed to program beneficiaries. In other words, it is money borrowed by the federal government from itself, but which it eventually, by law, must pay back to its citizens.

Government Debt in Context

As of March 2012, the amount of government debt held by the public was $10.85 trillion, and the amount of intra-governmental debt was $4.74 trillion, for a total national debt of $15.6 trillion.

And the U.S. national debt increases by roughly $4 billion every day.

The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) forecasts the gross federal debt at $16.3 trillion by the end of the 2012 fiscal year. According to a recent U.S. Treasury report to Congress, it will reach $19.6 trillion by 2015.

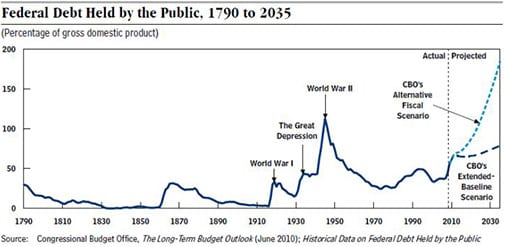

Staggering as the national debt figures are, without context, it is difficult to qualify the nature of the national debt and the part it plays in our country’s fiscal behavior. So one way in which the national debt has historically been evaluated and given context, is by examining its relationship to our country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP), which is the sum total of all goods and services produced in the nation in any given year.

Over many decades, the national debt’s percentage of the GDP has swung wildly based on various administration’s borrowing and spending habits. But every fiscal year that the government runs a deficit (spending more than it takes in), it has to borrow more money to fund its operations, thus bumping up debt’s percentage of the GDP. And we have run deficits every year this century.

During the George W. Bush presidency, debt held by the public as a percentage of GDP rose to 62 percent by 2008, as the gross public debt (marketable and intra-government securities) increased from $5.7 trillion to $10.7 trillion.

Under Barack Obama, the debt swelled to $15.6 trillion and its percentage of GDP topped 103 percent by March of 2012. That means that in 2012, our national debt will exceed our GDP – we now owe more than the size of our entire economy.

Another useful assessment that provides context for the national debt is its relationship to government spending: the U.S. government borrows about 42 cents of every dollar it spends. And approximately $1 out of every $4 dollars that it borrows goes to pay just the interest on the national debt.

Based on these assessments of debt’s recent enormous growth, its rising costs and its outpacing the GDP, there are those who believe that this economic dynamic is ultimately untenable. The Government Accountability Office (GAO), the federal government’s auditor, argues that the United States is on an “unsustainable” financial path and that serious negative repercussions will result if the debt problem is not addressed.

Political sparks flew in the summer of 2011 as Congress and the Obama administration battled over the raising of the debt ceiling, which is the legal limit of funds that the government can borrow in a fiscal year.

Evolution of Government Debt

The debt ceiling was first enacted in 1917 to provide a more flexible way for Congress to authorize debt. Under the Second Liberty Bond Act, it removed the need to approve each individual debt issuance separately and established a limit on the total amount of bonds it could issue and sell.

The debt ceiling has been raised 74 times since 1962 – 12 times in the last 10 years, alone. In 1979, the House of Representatives passed a rule to automatically raise the debt ceiling when passing a budget, without the need for a separate vote – except if and when it decides to waive the rule. It did so in 1995 and again, last year. The current debt ceiling of $16.394 trillion was authorized in January, 2012.

There is continuing public debate as to whether or not this huge government debt endangers either the country’s prosperity or its economic stability.

Potential negative consequences mentioned include the risk that a high debt level will:

- Undermine the nation’s ability to repay its loans in the eyes of its debtors, thus raising interest rates and the cost of borrowing more money.

- Retard economic growth and bring about increased inflation, especially if the government must print more money to pay its bills.

- Force the government to raise taxes in order to keep up with our interest payments and other obligations.

- Divert a growing portion of savings toward the purchase of government debt rather than investments in productive enterprises.

On the other hand, some argue that when the economy is as severely damaged as it was in recent years, borrowing money to pay for needed programs is more important than reining in debt. And that once the economic recovery is established there will be ample time to tackle the debt problem.

Others point out that because interest rates are so low, the debt service payment on the national debt (about $250 billion) relative to the size of the economy is less than it was throughout most of the past three decades – 1.6 percent of American output vs. 3 percent or more during the four administrations prior to Obama.

Regardless of how one views the extent of our national debt and the real or potential harm is it doing to our economy, here’s one more perspective worth considering: According to the U.S. Census Bureau, there are approximately 312 million Americans.

If the 2012 national debt is $16.3 trillion, then every American owes $52,244 to our country’s creditors.

Sources:

- U.S. & World Population Clocks. (n.d.). Retrieved April 30, 2012, from http://www.census.gov/main/www/popclock.html

- The Debt to the Penny and Who Holds It. (n.d.). Retrieved April 30, 2012, from http://www.treasurydirect.gov/NP/BPDLogin?application=np

- Monthly Statement of the Public Debt of the United States. (n.d.). Retrieved April 30, 2012, from http://www.treasurydirect.gov/govt/reports/pd/mspd/2012/opds032012.pdf

- Bureau of the Public Debt. (n.d.). Retrieved April 30, 2012, from http://www.publicdebt.treas.gov

- Congressional Budget Office. (2010, July 27). Federal Debt and the Risk of a Fiscal Crisis. Retrieved April 30, 2012, from http://www.cbo.gov/publication/21625

- Congressional Budget Office. (2011, June 22). CBO's 2011 Long-Term Budget Outlook . Retrieved April 30, 2012, from http://www.cbo.gov/publication/41486

- U.S. Government Accountability Office. (n.d.). Federal Debt Basics. Retrieved April 30, 2012, from http://www.gao.gov/special.pubs/longterm/debt/debtbasics.html#largefeddebt

- Fisher, D. (2010, February 8).The Global Debt Bomb. Forbes. Retrieved April 30, 2012 from http://www.forbes.com/forbes/2010/0208/debt-recession-worldwide-finances-global-debt-bomb.html

- Reuters. (2010, June 8). U.S debt to rise to $19.6 trillion by 2015. Retrieved April 30, 2012 from http://www.reuters.com/article/2010/06/08/usa-treasury-debt-idUSN088462520100608

- Karabel, Z. (2011, July 15). The U.S. is Not Drowning in Debt. Time. Retrieved April 30, 2012 from http://moneyland.time.com/2011/07/15/the-u-s-is-not-drowning-in-debt/

- You will need Adobe Reader to view the PDF Download Adobe Reader